Part I: Memes and Dual Coding

In its essence, teaching is the process of transferring new information to a student’s mind. This is a reductive definition and clearly there are many other issues that arise in the classroom. However, putting aside a broader conception of education, the above definition is a useful one. If a student leaves the classroom without new knowledge, it could be said that no teaching or learning has taken place, or at least not the desired sort. Effective practice in teaching is the search for the most efficient methods for achieving this transfer, which will differ depending on the subject matter and type of learner.

One major issue in developing effective practice is that of resource design. What should the resources that we use in the classroom look like? I believe the answers to this question can be unduly affected by cultural prejudices. Consider your gut reaction to the following questions: Should classroom materials bear more resemblance to a broadsheet or tabloid newspaper? Should they rely more on text or images? Should they look at all like the content people are sharing on social media? Questions like this are often belied by a discourse of highbrow versus lowbrow culture.

There is an idea that pages of dense text are more rigorous than those with illustrations, diagrams, or images. Is the student learning more when the information is presented in the most digestible manner possible, or do they benefit from struggling to make sense of information without aides? The latter attitude is a possible hangover from a time when the marginal cost of sharing information was not close to zero. The further back from the printing press and digital revolution, the greater the onus would be to cram in the greatest amount of text possible, giving rise to tomes with small text, cramped formatting and wafer thin pages. The inclusion of images and illustrations has only become more common in the age of mass-production. For some people, there is still a suggestion of laziness in resources that include graphical representations of information or even video as compared to more traditional, text-heavy sources.

Evidence-based teaching provides a useful basis for anchoring one’s teaching practice. One of the most useful and effective principles is that of Cognitive Load Theory. If you are unfamiliar with his theory, it is explained well here on TES or by the excellent Learning Scientists. What I’m interested in is examining how these principles are already at play in many modern-day aspects of our lives, and hopefully unearthing some practical advice on how they can be put to use in our teaching.

One of the most important concepts is dual coding (for more on this see Oliver Caviglioli’s website and work). Put simply, dual coding means that information is absorbed more easily if it is presented via two distinct channels: text and image. In this way, the mind can take on new information more quickly since it is being presented with stimuli in two ways that do not clash with each other. This principle is the reason why some people would find it hard to read if there is a loud conversation in the background, and why it’s usually a waste of time to read a large chunk of text verbatim from a presentation to an audience who can simply read it for themselves.

It can feel quite surprising that this is such a revelation in the teaching profession. It’s still very common to see slides and textbooks crammed with dense text. (It could be that teaching is able to get away with avoiding the most efficient approaches due to being a wicked-domain.) However, the principle of dual coding is evident in many common forms of communication. Everyday conversations use this principle. Speech is combined with paralinguistic features like facial expressions, gestures, body language and prosodic features like pace, volume and tone. This explains why conversations over the phone can be more prone to misunderstandings.

Dual-coding is evident any time information needs to be communicated quickly and clearly, especially those in which accurate and speedy feedback is paramount. This includes road signs, emergency information and advertisements. Perhaps one of the most totemic examples is the newspaper front page. In this domain, the aim is to influence the greatest number of people as quickly and efficiently as possible. These are especially effective in creating an impression of a public figure, even without the reader consciously engaging with the article itself. Columns of neat, thoroughly researched argumentation are likely not having the same impact as a carefully chosen image coupled with a punchy headline.

Dual coding also migrates very happily to more recent forms of communication. It helps to explain why instant messaging is often peppered with pictorial representations of feelings and reactions. Synchronous, conversational communication is usually clearer with the cues usually provided by facial features and gestures, as mentioned previously. Online, emojis and gifs stand in as proxies. The meaning of a simple message like ‘ok’ can be modified greatly by the inclusion of a different emoji. The emoji adds a cultural and emotional inflection to how the text message is intended and received.

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

As the internets favoured mode of communication, memes are another clear example of the principle of dual coding at work. In fact, this principle lies at the heart of these combinations of text and image that have become a cornerstone of the online world. In this frenzied, hyper-competitive space, communicating a concept quickly and widely has been honed to its essential components. Memes communicate so well that, just like a newspaper front page, you don’t have to consciously decide to read one in order to take in the information. Since the brain can parse the text and image simultaneously, the meaning is conveyed almost instantly.

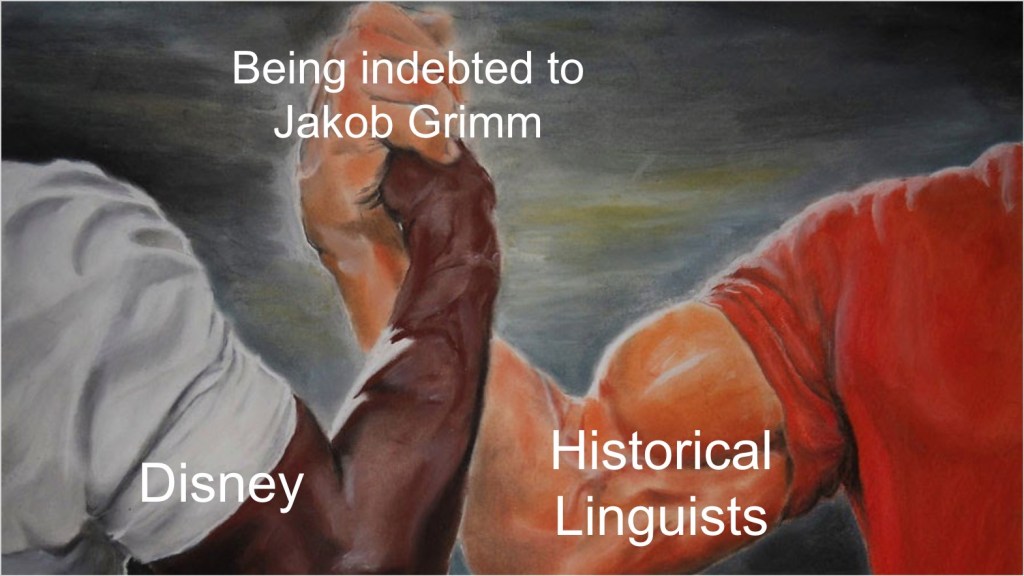

Dual-coding is not the only principle at the heart of the communicative power of memes. They also rely on other systems that make their messages so rapidly transferable. At their core, memes are a metaphorical form of communication. Not only does the image transfer information because it is pictorial, but also because of what it shows. More often than not, the picture element presents a more relatable or universal concept than the text. This is similar to Lakoff’s idea of conceptual metaphors. The language used to talk about an unfamiliar or recent idea are grafted onto another more fundamental and relatable set of concepts. Political debates are war, information is a physical commodity, or the internet is a navigable place, for instance. The images often relate to what could be called biologically primary knowledge or cultural universals. These are concepts that are fundamental to the human condition, whether they are the product of nature, nurture or a combination of both. Without formal education, most people raised in a human society will understand how navigation, hierarchy and emotion work.

The text, on the other hand, is where the newer, more complex information can be added. This allows novel ideas to be mapped onto already existing concepts in the receiver’s mind. No matter how obscure the domain, there is likely a group out there exploiting templates to make relevant memes. You don’t need to be a subject specialist in linguistics to understand the thrust of the following memes. They are based on fundamental human concepts of comparison, experience, physical strength, cooperation etc.

Original artist Shen Comix @shenanigansen

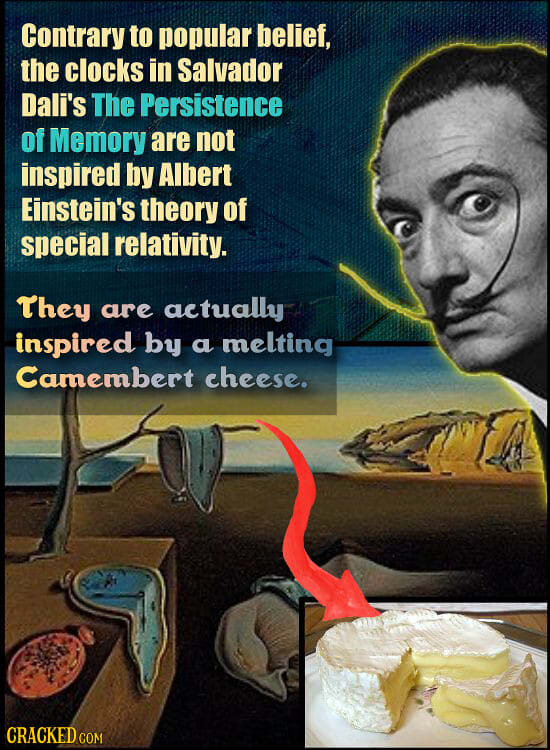

It seems undoubtable that memes share messages efficiently. The question is: what is the content? Tabloid newspapers, political advertisements and memes have another unfortunate commonality: the ability to spread misinformation or prejudice. It isn’t difficult to recall or discover disquieting examples of this, such as the Nigel Farage’s infamous ‘Breaking Point’ poster. This returns to my earlier distinction between ‘teaching’ and ‘education’. The efficacy of certain teaching methods is becoming clearer; the larger, more urgent question is what content should be taught? This questions is not to be explored here, save to note that it is a matter of political and philosophical contestation.

What does all this have to do with teaching? I think the above ideas should be taken into account when designing presentations and resources. (This is without even mentioning the appeal of video games and ubiquitous YouTube videos for young people). Of course, this depends on the level of the students you are teaching. If a learner is already an expert in a subject and can study independently, reading pages of dense text might be the quickest way to pick up detailed information. However, if your learners are novices or struggle with metacognition, dual-coding and metaphors based on cultural universals could make new ideas more manageable.

Many of the learners I work with are borderline grade 3/4 at GCSE English Language. Two major barriers that prevent them from attaining the pass grade are their lack of English Language subject knowledge and their lack of cultural capital. It’s very easy to ask a learner a closed question to check if they know what ‘personification’ means or what World War II evacuation refers to. Put in this position, learners will very often answer ‘yes’, perhaps to avoid embarrassment or because they feel that is what they are expected to do. Asking the learner to explain a concept and being prepared to always return to square one in order to explain it will ultimately help close the gaps which are holding them back. Taking the time to show a slide with a contextual image or sketching a quick diagram can save time and confusion in the long run.

https://www.cracked.com/pictofacts-1570-dumb-things-people-misunderstand-about-famous-works-art/

Ironically, teachers seem very slow at learning this lesson. In many typical lessons (my own included), the teacher will use a text-heavy resources. The teacher will provide two or three textual sources of information: their own speech (whether ad libbed or verbatim), the text on a set of slides, and printed handouts on the desk. The hope seems to be that more text = more learning. According to the principle of dual coding, this is not the most efficient way to share information. In this sense, resources could be more effective when they look less like a broadsheet newspaper and more like a tabloid or meme. However, the irony is that producing texts with appropriate images, symbols or diagrams is much more time-consuming than producing more prestigious seeming, text heavy resources.

Troublingly, teachers may end up having less control over what content is consumed in their classrooms. It has taken longer than many expected, but educational courses are moving gradually from textbooks and hand-outs to video and online, interactive content. It is easier and cheaper than ever to create this content, but still extremely time and resource intensive compared to creating resources based on static text. Most teachers and schools are more likely to buy it rather than produce it themselves. Who is producing it and what it contains will most likely be out of teachers’ hands.

This is an excellent read Luke, it should be a published journal article I think: possibly with a title related to what all teachers need to learn, or similar?

LikeLike