I’ve been an English teacher for over 10 years, working in the UK and overseas. English is my first language, I was born in England, and would happily say, “I’m English”. However, it’s rare that English the language and English the nationality enter the same conversation despite their obvious connection to each other. This post is an attempt to answer the question: does teaching English have anything to do with being English?

This is a contribution to a debate that has interested me ever since I did my first placement as an English tutor before starting my PGCE. Having grown up in Sheffield, it’s a topic that is impossible to ignore: the role of dialects and accents in the education system. As a student and teacher in Sheffield and Manchester, it was clear that the English language was more complicated than the subject taught in class. What stood out to me (and would later form the subject of my research) was how some features of language were acknowledged and celebrated while others were shunned or mocked. The more I learnt about language and education, the less this made sense. My views on this aren’t particularly original or new – the first post I made on this site summarises my take on the argument.

Among linguists and educationalists, there is a growing body research on the practices and outcomes of current language and education policy. It claims that a punitive approach to language education does not aid in language learning, and worse, denigrates and irons out the non-standard, but perfectly grammatical features of English. As commendable as this research is, it’s nothing new – calls for a different approach have been made regularly since the 1960s and earlier. In fact, the 1921 Newbolt report claimed that a pupil should not, ‘be expected to cast off the language and culture of the home as he crosses the school threshold’. Unfortunately, as we can see a century later, expert understanding of an issue does not automatically translate to broad consent. If any kind of change is to be realised, it needs to be joined to some kind of political project.

Previously, I viewed the above topic through the lens of my hometown of Sheffield or more broadly South Yorkshire and the North of England generally. However, it makes more sense to view this issue as something widespread and concomitant to some of the most fundamental issues at heart of English identity and governance. Having any discussion about English identity is not easy. It’s an idea that is so fraught that the most straightforward expressions of national identity like the flag of Saint George’s cross can be perceived as a symbol of racism, or a politician tweeting without comment a photo of a white van parked outside a house flying one caused a political scandal.

Like English identity, English language education in the UK is hotly contested. When it comes to the state of the English language, its grammar and mandatory testing, the debate is far from sober. It seems like there is an unreconcilable argument over the nature and purpose of the national language. Partly, this is unsurprising given contemporary reality of online media and the hunt for controversy to fuel clicks, likes and shares. Articles by linguists calling for greater diversity in language, and ripostes from traditionalists bemoaning attacks on ‘good English’ come round with clockwork inevitability. But there are deeper reasons as to why there is so little consensus. Teaching the native language of a country through compulsory education is always a political act namely since it is one of the key ways of forming the national identity. Decisions and attitudes about it don’t happen by accident, but are the product of competing interests and material realities.

Demands for a more linguistically diverse education system are nothing new. Putting the specifics of the case to one side, I wanted to look at the wider context and attempt to diagnose why the debate has been ossified for so long, and how it might be possible to take steps forward. These concerns are unlikely to be heard unless they take into account the current political context and are articulated as a set of demands. My argument is that given England’s unusual constitutional position and history, the English language’s unique role in world history, and recent political upheavals, the connections between the English the language and English the nationality are especially vexed. To understand why debate over language and education are so mired, it’s necessary to understand the context and structures under which British political and civic life take place. After outlining the historical and current issues that constitute the status quo, I will make some proposals for a more transparent, democratic and fairer settlement.

Issues

British Constitution

The British constitution is ambiguous – unlike many other countries, it is not based on a moment of national independence, civil war or revolution. In fact, it relies on the principle of ‘evolution, not revolution’. This means that in many areas the pace of reform is slow and there is not a rational or balanced approach to political decision making or oversight. Many norms and intuitions are pre-modern: the monarchy or House of Lords for instance. The UK is also one of the most centralised nation-states. Devolution has changed the situation somewhat, but even then, this settlement could technically be overturned by a future parliament. There is no constitutional principle securing local or regional democracy: as we have all recently learnt, Westminster parliamentary sovereignty is supreme.

This ambiguity causes stagnation in some areas, but also allows for rapid and far-reaching changes in the right hands. This ‘elective dictatorship’ allowed the Thatcher government to reshape the UK in fundamental ways: most recognisably through free market reforms summarised in the individuaistic declaration that ‘there is no such thing as society’. The Thatcher revolution particularly had major impacts on the regions of England. The outcome of the Miners’ Strike fundamentally weakened the power workers and unions, began the gutting of key British industries, and caused the long-term economic downturn of many areas in the North and elsewhere. In general, Thatcher’s instincts were to centralise and minimise the role of local government, a pattern that was repeated not only in the North and regions of England but also in London.

Governance in the UK seems to have two modes: uncodified bluster, often covering ingrained inequalities, and radical change from the centre with little accountability. Like Thatcher and Blair, Johnson has the parliamentary majority (coupled with royal prerogative) that allows him to make profound changes. This uncodified system and unwritten constitution have their benefits such as flexibility and decisiveness, but it also comes at a cost. Unscrupulous actors can rely on the public being distracted by the pomp and ceremony, and not examining the actual processes too closely, having faith that the UK will gloriously ‘muddle along’ as it always has done. The ongoing process of Brexit and reaction to the Covid-19 crisis are further testaments to this.

England in the UK

Another outcome of the UK’s ambiguous constitution is England’s unusual place in it. As the dominant member of the UK, England has often been happy to subsume its identity under the broader titles of the United Kingdom or Great Britain. From one view, this state of affairs is in England’s best interests. England is powerful, counting for the vast majority of land mass, population and wealth, as well as hosting and dominating the UK’s major institutions. However, by contrasting with the other constituent members of the UK, the position can appear more ambivalent.

Scotland and Wales each have its own parliament, national anthem, and unique language(s). These parliaments, for all their faults, mean that there is greater political representation and accountability. It is some succour for Scottish and Welsh nationalists that they are no longer entirely governed by the obscure, pompous and English dominated Westminster system. Both these countries have established policies that safeguard their Celtic national languages, both as a matter of linguistic equality but also in forming national identity and pride.

England, on the other hand, lacks many of the features that are normally associated with a nation: no unique parliament, no unique national anthem, no unique national language. England of course does have some national institutions and symbols: the Saint George’s Cross flag, English national sports teams, and the English language. In England, there is very little language policy to speak of, except from an imperial belief in the superiority of English and a lack of motivation to learn other languages. This is why English identity occupies a contradictory position: powerful yet also threatened — and why its few symbols are so hotly contested.

Language Policy

The aforementioned nature of the UK political system likewise impacts on language and education policy. Unlike many similar countries (such as France or Spain) there is no national entity in charge of the English language. In a similar way to the unwritten constitution, power is diffused between a number of elite institutions such as Oxford and Cambridge universities. Many people would see this as a good thing: it contrasts positively against the hyper-rational and formalised French approach, hopelessly battling against le weekend. Why would the UK even need an equivalent to the Académie Française governing body? – especially given the global dominance of the English language. Like many other areas, Britain is happy to muddle along with the English language’s adaptability and wide use around the world evidence of the success of such an approach.

However, such an ambiguous approach is again not without its downsides. The role of French as part of French national identity is closely safeguarded and strongly promoted. The role of English in British and English identity is less clear. Many English people would likely see the English language as being an integral part of their national identity. However, this simple claim belies several uncertainties.

One such claim being that there is such a simple thing as ‘the English language’. This phrase is really a semantic sleight of hand. Linguists would just be as likely to categorise English as a large language family containing many dialects or varieties. These varieties include national languages like American English, and social and/or regional varieties like African-American Vernacular English. This problematises the connection of the English language with English national identity. How can English be a marker of national identity when it’s the official language of several other countries and is spoken by over 1 billion people worldwide?

British Standard English

Given the lack of institutions, the linguistic settlement in England remains ambiguous. Like its constitution, the English language and its role in people’s lives remains uncodified. The official language of the UK is English, meaning that by default it is the official language of England. The version of English that is taught in schools and dominates in the media and professions is British Standard English (BSE). Evidently from its name, this is a British, rather than English confection.

British Standard English serves an important role in the UK and England. It is the standardised version of English, meaning there is a (more or less) agreed upon set of rules, including systems of spelling, punctuation and grammar. It is also the variety used in many professions such as the law, politics, health and academia, as well as being the language of much of media, literature and the internet. A major benefit of BSE is that it can be readily learnt and understood by anyone – whether they are from the UK or anywhere else around the world. For the UK, BSE serves a useful purpose – anyone from Aberdeen, Aberystwyth or Altrincham can access information, communicate with others, and (in theory) become a member of professional bodies and elite institutions.

Many books explaining the evolution of the English make the development of British Standard English seem like an inevitability. However, this is a misrepresentation. There is no historical destiny guiding the evolution of languages. How we interpret the evolution of languages and the policies we hold towards them is of course political. In the USA, the evolution of English in the British Isles can be seen as a mere precursor to its final form as American English – and African American Vernacular English as merely a bastardised offshoot, rather than a distinct variety with its own grammar and vocabulary.

The history of the evolution of language in England and the UK is complicated. The English language family we know today stems from several sources including Celtic, Germanic, Norse, and Norman languages, as well as borrowing from hundreds more. Before the industrial revolution and the technologies that would drive standardisation, there were countless dialects, accents, and spelling systems in England. The way people spoke and wrote English would vary between regions, towns and even sides of the valley.

Of course, modernisation and standardisation of language systems have obvious benefits like mutual intelligibility. However, in the long term it has also had a homogenising effect on language. Regional and social dialects and accents are dying out, and distinctions that do survive are becoming less varied in a process known as dialect and accent levelling. This ongoing process means that regional varieties of English are dwindling with one report claiming that Northern English dialects and accents could be lost within 50 years. The widespread negative attitudes towards non-standard varieties legitimises this process as a natural state of affairs, when instead it is the result of political decisions and broader societal inequalities.

Language Attitudes

As we have seen, British Standard English is not the full story of the English language in England. There are many other versions of English which we can refer to as dialects or varieties. These varieties are usually connected to a geographical area or social group. What also distinguishes them from BSE is that they are not standardised – and are therefore often referred to as non-standard dialects. For example, there is no dictionary to claim authoritatively whether the South Yorkshire adverb should be spelt ‘reight’, ‘right’ or ‘reyt’.

This nomenclature is where one of the general misconceptions about language comes in. For a linguist, any variety – whether that be BSE, Scouse or Multi-Ethnic London English – are all equally valid, grammatically speaking. They each have a consistent grammar system and can be used to communicate meaningfully. What distinguishes BSE are that it is standardised and that it is widely used; it is in no way linguistically superior. However, in popular imagination (and for some newspapers and political parties) the term ‘standard’ has taken on the meaning of ‘gold standard’. It is thought that BSE is a linguistically superior version of English that some how ‘makes more sense’ or is ‘clearer’ than ‘lazy’ or ‘incorrect’ versions. Of course standard can also imply something that is the default or even subpar as in ‘bog standard’.

In popular imagination, the English language is seen as the domain of society elites. As mentioned, there is no official institution with authority over the English language. This role therefore has fallen to elites groups and institutions, a number of whom are self-appointed. In many instances, institutions like Oxford and Cambridge play a laudable role in recording and disseminating materials on the standardised variety of the English language. However, by ceding authority over the English language to elites, a bias is given towards privately educated, middle-class modes of being.

The proliferation of popular grammar books like Eats, Shoots and Leaves and the popularisation of the term ‘Grammar Nazis’ are emblematic of a punitive understanding of grammar. Features of non-standard varieties are often used as examples of mistakes despite the fact that they are completely grammatical form a linguistic perspective. In popular culture, already dominated by privately educated Oxbridge graduates, a social or regional accent and dialect can unfortunately still often represent to the audience an uneducated or moronic character. Even France, with its strict approach to language policy, has laws against regional accent discrimination far beyond what exists in the UK. Ironically, when an advert, TV show or film wants to portray a sense of honesty or authenticity, it is often with the help of accent coaches and voice actors using or portraying English regional accents.

Language and Education Wars

All the above means that, like other areas of British political and cultural life, language and education policy is a political football that defies consensus. The two-party adversarial style of Westminster politics exacerbates this trend and is repeated in wider society. Debates can be often characterised by the addition of the suffix -war, whether that is the ‘grammar war’ between descriptivists and prescriptivists, or battles between (and among) teachers, schools and politicians raging on both traditional and social media. Battle lines between liberal and traditionalist educators are deepening with issues like exclusions, detention booths, direct instruction versus student-centred learning acting as key dividers.

English language education is of course not immune to such polarisation, especially considering the symbolic role that language plays in national identity. A cursory glance at England’s national newspapers will reveal the role of language and education surfacing frequently as a topic for debate. To over-simplify the two sides: the right-leaning side decries interpretations of standard English as prejudiced or even racist, and emphasises the need for maintaining rules and consistency. The left-leaning or liberal side states that language is constantly evolving, citing many previous rules that have fallen out of use, and urges people to accept more recent linguistic changes as valid such as the many uses of ‘like’.

The more conservative, prescriptivist outlook appears to have won out, unsurprisingly given that the last Labour government ended over a decade ago. Micheal Gove’s impact as Education Secretary was far-reaching with a grammar, punctuation and spelling test introduced at primary and a greater emphasis on accuracy across later qualifications. The war continues unabated, especially after lockdown with many parents shocked at the technical difficulty of the grammar tests when suddenly faced with the fronted adverbial which has long acted as a lightning rod for complaints. Even while writing this piece, this debate was reignited once again with Lord Digby Jones’s criticism of the accent of Olympic commentator and professional footballer Alex Scott.

In the classroom

The Conservative government has made some attempts to engender nationalistic pride and civic duty via the education system. Much of this has been controversial. An early reform, unpopular with teachers, was to remove any non-British authors from the curriculum. However, one of the most noticeable changes is the requirement to teach learners about ‘British Values’. Ignoring the underlying assertion that these values are somehow uniquely ‘British’, the actual content is largely positive: tolerance, democracy, the rule of law etc. Other attempts have been less successful such as the somewhat unsettling One Britain One Nation song. Clearly, the classroom is a site for nation building in the UK more than ever.

Given the lack of singular authority and ambiguous constitutional settlement, it’s hard to assess exactly what is happening in classrooms with regards to different varieties, dialects and accents of English. In response to the last decade of prescriptivist leaning reforms, there is a re-emerging body of research on how punitive attitudes to language are affecting pupils, especially those already disadvantaged. For instance, see the recent English in Education special issue on grammar in schools. However, these approaches appear to be fighting against the current.

Many of the dominant trends in education (such as academisation, league tables, high-stakes assessment, and an instrumental ‘whatever works’ attitude) encourage a one-size-fits-all approach. Teachers may be encouraged to see anything other than British Standard English as ‘incorrect’ or ‘bad’ English, standing in the way of mastery and ultimately better exam results. Of course, in a sense, they are right. But what is the cost of such an approach? We don’t know how much non-compliance or ‘common sense’ is prevailing over harmful and misguided zero tolerance policies such as ‘slang bans’.

English classes might be thought of as places for creativity and expression, but given the managerial and technocratic approach to education, they often become more and more about assessment and measurement. Again, this is not necessarily a bad thing. The fundamental question at the heart of English, or any other subject, is: How do we fairly and accurately measure our learners’ ability? What does ‘being good at English’ look like? These questions are not easy to answer and there will always be a debate and unavoidable trade offs in finding a fair and practicable balance.

Do we have the balance right now? What does ‘being good at English’ look like today? The range of proxies we could use is bewildering: knowledge of grammar, accuracy of punctuation, finding information in texts, producing creative stories, cohesive paragraphs, comparing, evaluating, analysing etc. etc. Again, aspects of national politics and identity enter. Can you be good at English and never have read any Shakespeare? It’s impossible to address all these issues here. However, I do believe that we are prioritising some proxies needlessly over others.

In the USA Spelling Bees are popular. In the UK, accurate spelling is one of the major proxies for being good at English and is thought of as a marker of intelligence and education. Errors can cause social embarrassment and could even cost people their livelihood. In other countries with phonetic languages, spelling bees or tests in school are not necessary since their language uses a regular, consistent system. Any Spanish speaker who hears a new word should be able to spell it correctly. Is memorising the ‘rules’ and exceptions of a notoriously counterintuitive and inconsistent system really a good measure of intelligence? It’s a difficult thing to achieve, but persevering with a difficult task does not automatically make you intelligent. For many people, isn’t the more intelligent option to rely on spellcheckers or simply to communicate without worrying too much over whether its spelt receive or recieve? We should bear in mind that spelling standardisation is a relatively recent notion, and that in the majority of circumstances perfectly reasonable spelling variations do not hamper communication.

Inequalities

If pre-modern institutions and ‘evolution not revolution’ are one side of British politics, perhaps the other defining aspect is inequality. Since the 1970s, inequalities across many areas of society have increased greatly. One obvious expression of this is through geography. London and the area surrounding it (the South East of England) have prospered, while many regions of England have seen decline. The IPPR report on the State of the North makes the situation starkly clear. But this is not simply a North/South divide. The divide is also present between rural areas, towns and cities, and within cities across class and race lines.

It’s not a coincidence that the area of the country that have seen its wealth increase is the same area that is the source of British Standard English: the ‘golden triangle’ of the South East including Oxford, Cambridge and London. There is a vicious cycle in which greater investment is justified on the basis of greater productivity, which continues to drive longstanding inequalities. The inequalities – economic, geographic and linguistic – run in parallel and mutually constitute each other.

The end result of these inequalities are manifest in the education system and wider society. For example, a recent parliamentary report cites multigenerational disadvantage, regional underinvestment and disengagement from the curriculum as reasons behind the relatively poor performance of working-class white boys. A proposed solution to this is to improve the cultural capital they have access to. In practice, this can lead to quite ham-fisted attempts to achieve greater equality – that by mimicking the cultural modes of those with greater wealth and power, disadvantaged people will some how acquire the same material benefits. Reintroducing latin is not going to reverse decades of neglect and underinvestment.

Oxbridge educated figures like Stephen Fry, Susie Dent, or even Boris Johnson, act as cyphers for educated and good English. These figures have permission to play with language, to coin new terms and rediscover words that have fallen out of use. For learners, such a creative approach to lanaguage can lead to punitive results if they fall afoul of the demands for accuaracy in a mark scheme. If an elite figure shares an obscure word whose meaning is not widely known and has fallen from general use, they are celebrated for their ingenuity. However, a young person can use a word or grammatical structure in their work – a feature that is likely used by their friends and family, and one that (of course) has an etymological origin as longstanding as any other – and be penalised for it. The irony is further heightened since obscure ‘words of the day’ are often relatively recent inventions of 19th century prescriptivists playing with Greek and Latin loanwords. Of course there is nothing wrong with this – but why are these words given priority over those with say Cetlic, Norse, Germanic, or even Gujarati or Jamaican origins?

Imperial Past

It would be impossible to write about English nationalism and identity without mentioning race and empire. That said, it is not my area of expertise, either from personal experience or research. However, a few tentative ideas seem worth mentioning.

Again, England and the UK occupy quite a unique position. There is no independence day to celebrate or establishment of a new political order. World War II and Brexit feature highly in the popular imagination as heroic stands, but the centuries of colonising other nations and peoples are rarely acknowledged. The task of dealing plainly with the legacy of empire and its consequences has barely begun. Still, the echos of empire have an effect on attitudes held by many English people. Unsurprisingly, the English language is a frequent touchstone for far-right nationalists who long for the glory days of empire.

People in the UK, like many others in the West, can see themselves as above history. It’s comforting to imagine your culture as the pinnacle of world history. In a similar way, English is seen as a clear and logical language that, along with the legal system, parliament and railways, was a gift to the rest of the world. Just like the Empire, English ‘borrowed’ widely from the countries and cultures it made contact with. The English language is by default the global lingua franca – English displaces other languages, not the other way around. The idea that some element of English would need to be protected or promotes is somehow hard to imagine. England’s early industrial revolution and embrace of modernity means that England sees itself as the global metropole. English is the language of the observer or the collector – it is for other obscure and exotic languages to be placed under the microscope or pinned to a board, to need documenting, reviving or saving.

Of course, these ideas do not bear scrutiny when compared with reality. English is a poor candidate for a global language – a hybrid of several sources with a spelling and phonemic system as boggling as German cases or Chinese tones. In fact, Welsh – a language often maligned by English speakers for its apparent complexity – follows a more consistent spelling and phonetic system than English. Similarly, it’s not unusual for English speakers to highlight ‘unusual’ sounds in other languages like the Xhosa click of Spanish or Scottish ‘throat clearing’. But the ‘th’ phonemes common to English are relatively unusual themselves – and it are routinely avoided in Irish-English, Yorkshire, Cockney and by non-native speakers of English.

The consequences of such attitudes are clear in the rigid monolingualism and general paucity of ambition with regard to learning foreign languages. Children in the majority of the world grow up speaking several languages and switching between them when necessary. Children in the UK who speak other languages and varieties of English are already adept at code-switching when necessary, but aren’t given the insight to understand the complexity of what they are achieving. Quite rightly, there are ongoing campaigns to make the texts studied in classrooms more diverse and from writers of colour – which will also most likely include writers from around England and the UK who use regional and social varieties of English.

For many learners in England monolingualism is not the norm. Precious hours at the weekend are spent on extra studies – language and cultural classes on their family’s original country. Extracurricular Polish, Arabic or Tamil classes may often be resented by those forced to take them, but they are an important way of maintaining generational and cultural ties. The necessity of such classes reveals the assumption that for white, British, middle-class learners, your cultural and linguistic assumptions are the default and will be present and validated by the mainstream curriculum.

Brexit and Experts

The impetus behind the Leave vote can be interpreted in many ways. Putting aside the obvious – legitimate and long-standing criticism of the EU and the belief that the UK would prosper outside it – two more intriguing strands emerge. One is the little Englander, anti-immigration interpretation. The other is as a general rejection of the status quo and an opportunity to throw a spanner in the works of the elites – whoever precisely they may be. England’s unusual constitutional settlement means that there are few avenues to express discontent or to hold decision-makers to account. In some respects, the Brexit referendum, with every vote counting equally, was an opportunity for some who felt they have lost out to simply vote ‘no’ – ‘no’ against the status quo. It was a rare chance to have an impact on the fundamental direction of British politics.

One of the most memorable soundbites from the Brexit campaign was Micheal Gove’s claim that ‘people have had enough of experts’. In an age of rising populism such a statement does resonate. Obviously, where this slides into conspiracy theories and prejudice, it’s not to be countenanced. But Gove and others did identify and channel a dissatisfaction that quite rightly identified that many of the narratives people were being told in the mainstream media did not regularly chime with the day-to-day reality they experienced.

There are many such sacred cows in British society that have not been sacrosanct for some time. For example: a university education guaranteeing well-paid work, that the UK is a home-owning democracy, that wages and standards of living will be better for your children. For many people the purported benefits of globalisation – with membership of the EU being a key signifier – was that a rising tide would lift all boats. In reality, for many people in the UK, if not most, this has not been the case. Unfortunately, unscrupulous actors uses immigration, as an especially visible outcome of globalisation, as a scapegoat for the wider lack of progress.

This ‘had enough of experts’ attitude could also easily apply to language and education policy. It’s already visible in the vocal dissatisfaction with primary grammar tests. It’s exacerbated by England’s unclear constitutional and linguistic settlement. Education is sold as a great leveller, when in truth, it’s common knowledge that people who speak a certain away – alongside displaying many other middle-class signifiers – are more likely to be successful, take part in elite professions, get on the property ladder etc. The recently reformed GCSE English Language qualification has been criticised for being a test of middle-class knowledge given that it relies on analysing an unseen text chosen by a presumably middle-class cohort of examiners.

Brexit goes hand in hand with the rise of identity politics. For some people, the ideas of freedom, independence and national identity were more important than the material reality of reduced freedom of movement, less trade with our nearest neighbours, and poorer economic performance in general. Most people don’t want to see themselves as human capital in a globalised market. Despite how it may feel to the mobile middle-class, almost half of British adults still live in or nearby their hometown. They want their lives, education and work to be meaningful and connected to the places they live and the people they care about.

In many instances in British society, people intelligently distinguish between publicly proclaimed rules, and the widely-understood reality. For example, drugs. Aside from alcohol and tobacco, mind-altering substances are illegal in the UK. However, it’s common knowledge that many public figures have taken them, including serving politicians. Ordering and receiving drugs not only from the dark web, but from a normal web browser, is trivially easy, and the UK drug market is estimated to be worth around £10bn. Generally, the people who are penalised for this fact of life are those caught up in dealing, predominately young and from disadvantaged backgrounds. Politicians, teachers and pupils may nod along to the pretence that the situation is otherwise, but that is merely for appearances.

These kinds of pretences may be necessary for a liberal democracy to function. However, they have their limitations. This was revealed starkly during the Covid-19 lockdowns by the varying degrees to which people felt compelled to follow the rules and the worryingly large number of people taken in by conspiracy theories. We are also in a similar situation with English language education. Most people see that the many of rules they were taught in English class are really not so important. It’s extremely rare that a misspelling, butcher’s apostrophe or use of ‘of’ instead of ‘have’ in the present perfect, has ever led to a genuine miscommunication. More likely the only downside would be criticism from an interlocutor who assumes that memorising arbitrary rules is a fair measure of linguistic ability or general intelligence.

The above confirms a suspicion that is not often articulated, but I imagine widely felt. The kind of English you are taught in English class is not a accessible, knowable subject, but a shibboleth for middle-class habits and customs. Anecdotally, I have witnessed the attitude that while some pupils ‘just get’ English, the subject is simply ‘not for’ other learners who are often classed as ‘less academic’. For many pupils, English is a mysterious and endlessly subjective class that has to be tolerated until GCSE at which stage, by hell or high-water, you cram and practice to get the grade 4, before then charade is dispensed with. In the age of smartphones, instant communication and social media, experimentation, remixing and juggling varieties is the norm. Intelligent and articulate young people go on to work, communicate, and make lives for themselves using language as they see fit, while the grammar they were taught in school becomes largely forgotten.

Regionalism and Levelling Up

In the wake of Brexit and Covid-19, the Conservative government under Boris Johnson is pivoting. It hopes to be seen as the party of the ‘red wall’ northern seats that dropped Labour in their droves and handed the Tories power. This means greater investment in England’s regions that will deliver on the slogan of ‘Levelling Up’. This is already looking less like a fair-handed rebalancing of the British economy and more like pork-barrel politics to guarantee that these constituencies vote the same way in the next general election. Without the bogeyman of the EU nor the quite real EU regional funding, the Conservative party will have to make good on at least some of these promises to stay in power. However, many Leave voters may discover that they have dispensed with one unaccountable political system, only to be confronted with another.

Of course, Levelling Up is not the first catchphrases meant to deal with England’s regional divide. From Blair’s regeneration and his abortive attempt to start regional government in the North East, to Osborne’s sloganeering about the Northern Powerhouse, politicians are at least capable of recognising the problem. However, the actual record is spotty at best. England now has a patchwork of city-regions and mayors, and a handful of national institutions have been shunted to various regional cities. None of this amounts to a cohesive political programme or comes close to devolution afforded to the other constituent members of the UK. The regions of England suffer from chronic underinvestment and decades of economic stagnation. Special economic areas and reductions in standards and working conditions are not the answer.

Despite this slow progress, there have also been signs of a ‘bottom-up’ reimagining of English regional identity and pride. For example, a recent survey found that people in Yorkshire identified as strongly with their county as with their national English identity. In the face of the closure of regional newspapers, much independent local media is flourishing. There is also a trend for regional dialect words and phrases to be emblazoned on clothing, and artwork featuring iconic local architecture. In more material terms, the Preston model of community wealth building has delivered undeniable dividends for the city, in contrast to the majority of councils suffering under continued cuts. Political parties like the Northern Independence Party and Yorkshire Party have also been established, although neither is close to winning a Westminster seat. By contrast, Andy Burnham has made great use of his role as Mayor of Greater Manchester to improve the city and raise his profile. If there is a nascent appetite for English regional identity and democracy, it is unlikely to be served by the piecemeal city regions and special economic areas we have seen so far.

Technology

A theme in this piece has been globalisation. One of the key drivers of this process is the communication revolution powered by the internet. The technological utopia imagined a global village in which people would communicate around the world, information would be readily available, and old silos such as the nation state would become defunct. Although some of the above prophecy has come true, this utopia is far from a reality. Despite its name, globalisation has also lead to greater regionalism and localism. And with the end of freedom of movement under Brexit and the possible long-term effects of Covid-19, the turn towards localism could be set to continue.

Most people probably have not used social media to reach out to someone on the other side of the world, but they have used it to talk to people in the same town or neighbourhood. Facebook groups and location-based social media such as NextDoor provide people with a way to connect to the people who live nearest to them – in some respects filling the gaps caused by ongoing social atomisation and alienation. Ecological concerns mean that websites and apps that allow people to swap, rent and buy second-hand goods or collect near out-of-date food are also on the rise. These technologies also allow for a revival of social and regional dialects. On social media, language is not policed like in school and other institutions, making for more genuine expression. Social media allows videos of young children switching between parents’ accents, or explanations the subtleties of tense in African American Vernacular English to go viral – further eroding the reliance on distant experts.

However, technology also contributes to the trend of language standardisation. Many digital technologies have emerged with the aim of helping people to write more accurately: predictive text, spellchecker, programmes such as Grammarly and AI writers. Such technologies are more than likely to be created by programmers and designers in silicon valley. These technologies are therefore not sensitive to the idea of regional and social varieties of English, but rather see ‘the English language’ as singular, knowable entity with ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ forms. This standardisation by stealth is undoubtedly having a chilling effect on English speakers who are corrected for using non-standard forms, and are now used to trusting Google or Microsoft as authorities. As I explored in a previous article, these technologies unfortunately flash-freeze whatever biases and prejudices are held by their designers, as anyone with a regional accent who has attempted to use a smart speaker can attest.

Alternatives

For ways out of this mire, it is illustrative to look at close neighbours. Some nations, like France and the USA employ similar policies to the UK, emphasising the use of a single prestige variety at the expense of others. However, it is not hard to find less restrictive examples. One such model is Spain. Spain’s constitution was established on a principle named cafe para todos (coffee for everyone) that divided the country into autonomous communities and gave the same powers to each, including ones with separatists ambitions like Catalonia or the Basque Country. Every comunidad autónoma has the democratic mechanisms necessary to create language and education policies that promote local and regional varieties as seen with the resurgence of the Catalan and Basque languages.

Closer to home, Scotland pursues a similar set of language policies. These are not only in regard to the Celtic language of Gaelic, but also the variety of English called Scots. Evidently, having a more varied approach to languages and education is achievable. English regions would be more than capable of formulating similar education and language policies that serve each local situation, rather than spectating on a far-away and never-ending debate. By giving regions some power over education and language policy, the issue becomes less politicised and polarised in a similar way to the Blair government granting independence to the Bank of England or making a Supreme Court separate from the House of Lords. The question this poses is: What would a more inclusive, fairer and democratic approach to English language education in England look like? Can England be a ‘normal wee country’?

Returning to Catalonia, the former president Jordi Pujol once remarked: “They are Catalan, whoever lives and works in Catalonia and wants to be it.” The idea behind this statement is that Catalan identity is not based on ethnicity, but on language and location. The same could apply for England: Whoever lives in England, makes their life here, and speaks English is English. A similar idea extends to the English language as spoken in England, making it distinct from BSE. The English language in England as a product of English people at large, who should see themselves as custodians of the English English language as well as its culture, history and heritage.

Of course, it is not a single culture, history and heritage. The danger is to create an exclusionary idea of Englishness based on its ancient origins: that to be English is to be ethnically Anglo-Saxon or perhaps Nordic. The last thing I want to promote is English exceptionalism or white supremacy. But the response to these despicable ideas can’t be to concede England’s history to the far right, but instead to call them out and reclaim it, as is being debated in archaeology. The English body politic and language has long been the result of diversity: the mix of Celts, Romans, Germanic tribes (including Angles, Saxons, Jutes and more), Vikings and Normans does not make for ethnic nor linguistic purity. More recent arrivals in the wake of British Empire and globalisation are undeniably a further part of English language, culture and history. Instead of scrambling for a narrow vision of cultural capital, English regions should be drawing from and creating their own broad linguistic and cultural richness.

In terms of education, the core of a more inclusive approach relies on critiquing the deficit model of education. Briefly, the deficit model sees learners as arriving to the education system somehow lacking. The teachers’s and education system’s role is to change and replace the knowledge learners arrived with and to transform them into something different or better. Critiques of the deficit model emphasise respecting and celebrating the knowledge that learners come to school with and incorporating it into the curriculum.

I wouldn’t simplistically criticise deficit thinking in all areas of education – patently, we want learners to leave school with a more scientific understanding of the natural world or more sophisticated skills in maths than they arrived with. However, in the ambit of language, the pendulum has swung far into the deficit side, creating a system that is not linguistically sound. The ways of speaking that learners bring to school are by definition valid as long as they are able to communicate. Yes, pupils should be taught the conventions of BSE, but this should not come at the cost of denigrating other forms of English they use at home, with friends, online and in creative expression. The language, words, grammatical forms, accents and modes of being that learners bring to the classroom are assets – they are valid, grammatical and meaningful. They are a repertoire to be drawn from with the selection of the appropriate variety and register contributing to communication in vital and persuasive ways. Not to mention the value that any variety of English (or other language) has as an object of study in itself.

To take the above approach, many attitudes and practices in schools would have to change. In short, schools (and wider society) should actively combat linguistic prejudice. Policing the way pupils speak and write in all circumstances is not only unhelpful, it is also harmful. No matter what language, dialect or accent learners (and staff) come to school with, they should expect respect. Learners putting their hands up in class should be judged on the content of their ideas, not the words and phrases they use to express them.

That is not to say that there isn’t a role for British Standard English in schools. Children should be taught to use the prestige variety of English – one of the better arguments in favour of this being the case for greater equality. However, equipping students with the ability to understand and produce a standardised variety of English does not need to come at the expense of other versions. Better to stop persecuting wars over the English language and instead to accept the reality of linguistic diversity while also accepting that countries and societies will always attempt to corral language in some way.

To clarify the situation, it would make sense to establish an agreed upon version of British Standard English for schools. This variety would be reviewed regularly by an institutional authority. This would establish a version of English that is truly transparent and accessible. The majority of assessed work in English and other subjects would be expected in this variety, where appropriate (e.g. essay or report writing, formal speeches). This allows British Standard English to fulfil the educational role the prescriptivists defend: a version of English that is open to all and allows access to and potential membership of academic, legal, media, political and civic professions. This is still somewhat unfair to learners who do not generally use the prestige variety, but that doesn’t change the importance and ubiquity of British Standard English.

If we are going to use one variety of English as a prestige dialect, we should at least be straightforward about it. BSE is a standardised version of English – nothing more and nothing less. Many learners enjoy learning the rules and conventions especially when they feel welcomed to the ‘club’. Pupils and parents often take pride in having access to and being able to use the ‘proper’ version of English. A standardised version of the language also means there is a measurable, testable and comparable version of the language – a somewhat contrived version, but useful nonetheless. BSE is an asset for all learners to acquire because of its useful function in society, not because of linguistic superiority. If there term ‘standard’ is often equated with ‘gold’ or ‘high standards’, we should also remember that it is term for the ‘default’ or ‘expected’ – the ‘bog standard’.

In this vision of education, it would be necessary to establish some rules and norms that go against the current grain. A start would be to create a framework in schools (and wider society) which prohibits accent and dialect prejudice. Specifically in schools, slang bans, injunctions to always speak ‘proper English’, using non-standard forms as examples of ‘bad’, ‘lazy’ or ‘incorrect’ English, instructing teachers and staff to change their accents and similar misguided policies should become a thing of the past. But this approach should not only be oppositional, but propositional. For the general public, seeing talking heads calling out racist, sexist, classist views is not enough and can come across – or be misconstrued as – petty name-calling or ‘cancel culture’. English language education policy should not be a list of things we can’t do, but an ambitious, audacious repertoire that draws on the richness of the Englishes in England and gives learners powerful knowledge and skills.

Now the role of BSE has been clarified, we are free to consider the role that other varieties could play in the education system. Pupils should learn about other versions of English besides British Standard English, and should especially learn about versions of English spoken in their locality. These could be referred to as English varieties, or dialects. This includes general non-standard English, regional and social dialects and accents, and world Englishes. This broader conception could even include other languages – for example Celtic, Modern European and Community languages – especially where they cross over with English. In this context, knowledge of grammar and metalanguage can be empowering rather than punitive. If a learner can work out the grammatical form or function of dialect or ‘slang’ words, it becomes harder for others to delegitimise them in their eyes. This would be a broader, more creative approach to language education, and one that is clearly distinguished from its standardised cousin.

The potential topics of study are multiple:

- The vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation of non-standard varieties

- Comparisons with British Standard English, and other varieties and languages

- Origins, etymologies and language evolution

- Connections to local and regional history and heritage

- Dialect and accents in media, literature and the arts

- Language attitudes and prejudices

Learners would also have the opportunity not only read, but to produce work using non-standard varieties of English. This would be clearly differentiated from using British Standard English. Perhaps this kind of work would not be assessed, or at least would be assessed on a very different rubric – one that prioritised creativity and expression over accuracy. Learners would have an opportunity to play with language and to experiment with spelling, syntax, and pronunciation, which could also contribute to a better understanding of standard forms. For activities, pupils could write poetry reflecting on their idiolect, imagine a letter written by a local historical figure, pen and perform a grime verse, compose dialogue with characters discussing local issues, or create adverts for local businesses making puns with regional vocabulary.

Such an approach poses a challenge for the education system. It prioritises knowledge that is local, changeable and not in the hands of elite authorities. The knowledge involved is not one-size-fits-all, cannot be scaled or assessed in standardised tests. The work produced would not be useful for comparing pupils or schools. The work that pupils produce needn’t be marked in a traditional sense, but is instead acknowledged, critiqued and celebrated. One way this could be achieved would be through comparative judgement, with pieces being read and ranked by local pupils, staff and the wider community. The knowledge that is prioritised is local and contingent, and teaching would take a more bottom-up, generative and emergent approach.

A common retort to a more diverse approach to English language teaching is that learners would struggle, that it would harm their native language or ability to master BSE. Monolingualism is so entrenched in England that it’s easy to assume that learning other languages and varieties will be an insurmountable challenge for most learners. This point of view is to drastically underestimate the capacities of young people in England especially when compared with the majority of other countries. Examples are not difficult to find such as 10 year old Abdullah who moved to Scotland from Syria and not only learnt English but also Gaelic. To a multilingual outsider, England’s lack of ambition when it comes to languages is probably quite puzzling.

Such an approach as described above would of course have challenges. Traditionalist or even prejudiced language attitudes are pervasive in the UK, and strongly held by many parents, teachers and staff. Hopefully, we can create new norms based on balancing the importance of learning BSE against respecting the diversity and heritage of other forms of English. New resources would also need to be created. These resources can be cross-curricula, drawing from history, geography, literature, language and, importantly, local knowledge. As much as schools now make sure to open their hiring process to those with disabilities or from minority backgrounds, they should also see staff with local accents and dialects as an asset. Learners and staff also need to know how to use technology, when to rely on it, when to switch it off, but also to create videos and digital content that preserves and celebrates their local and social varieties. More broadly, the way we teach and assess English will always be contested, and whatever proxies we agree upon will always be a compromise. But at least, such an approach may start to better reflect the linguistic reality of England.

Conclusion

Knowledge of language and grammar can – and should – be empowering. I’ve been fortunate to have several opportunities to study language and education at greater length than most. These studies have taught me that the dialect of Sheffield and South Yorkshire is not ‘incorrect’ or ‘bad’ English, but instead a valid and grammatical variety with greater influence from Angle and Viking settlements, sharing many cognates with Scandinavian languages, retaining pronunciations pre-dating the vowel shift, and having some features that add more precise meaning that BSE, such as with the second-person Subject and Object pronouns. The real shame is that this kind of straightforward knowledge about regional varieties of English is seen as arcane, only for A-levels and above, when instead it is part of millions of people’s daily life and heritage. Would it really be so hard to engender an English identity that accommodates this diversity and heritage?

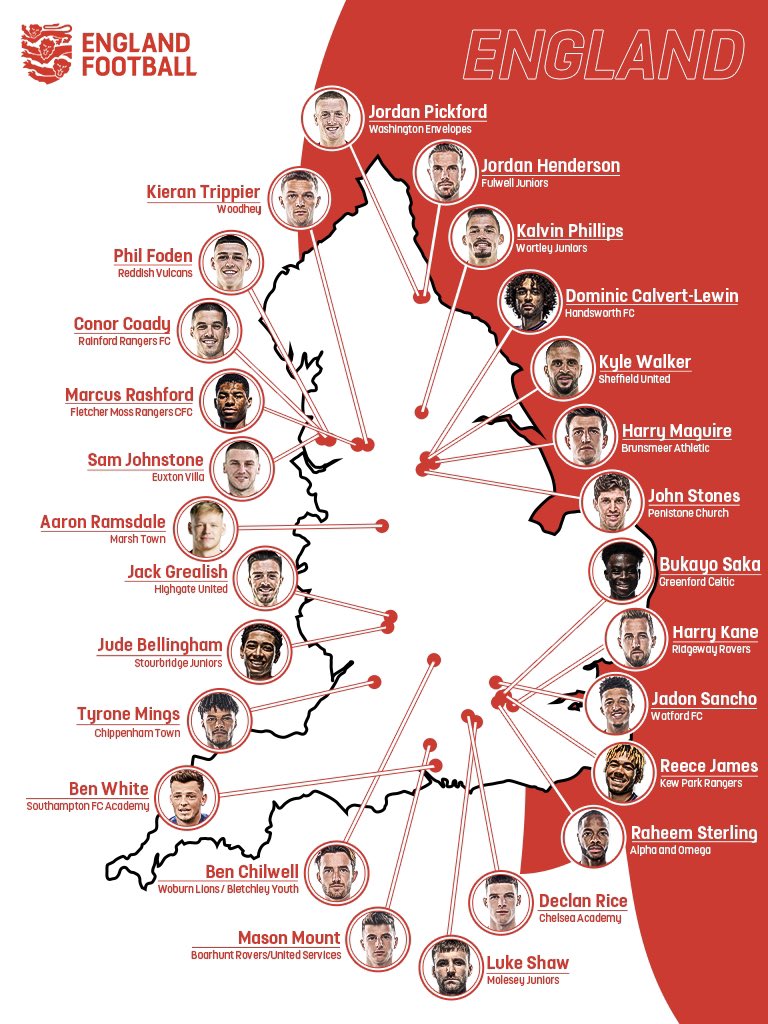

It’s irresistible to write about English identity and nationalism without making some reference to the England men’s national football team – unsurprising, considering that it is one of the few distinctly English national institutions which captures the popular imagination. Recently, the beautiful game itself became a political football, subject to a familiar polarisation of opinion. After the dispiriting criticisms of taking the knee and the disgusting racist abuse after England’s defeat to Italy, many in the government and their outriders in the press were hastily backtracked on their criticism of the ‘woke’ team. As has been mentioned often before, the England squad and manager Gareth Southgate present a positive image of English nationalism and identity: principled, hardworking, fair and inclusive. The team is diverse with more than half having family born outside the UK, and players themselves hailing from across almost all of England’s regions. This vision of Englishness could be adopted more broadly – a report by British Future backs this up, finding that the Three Lions is the English symbol that most people identify with and that most consider that English identity is open to to people of any ethnic background.

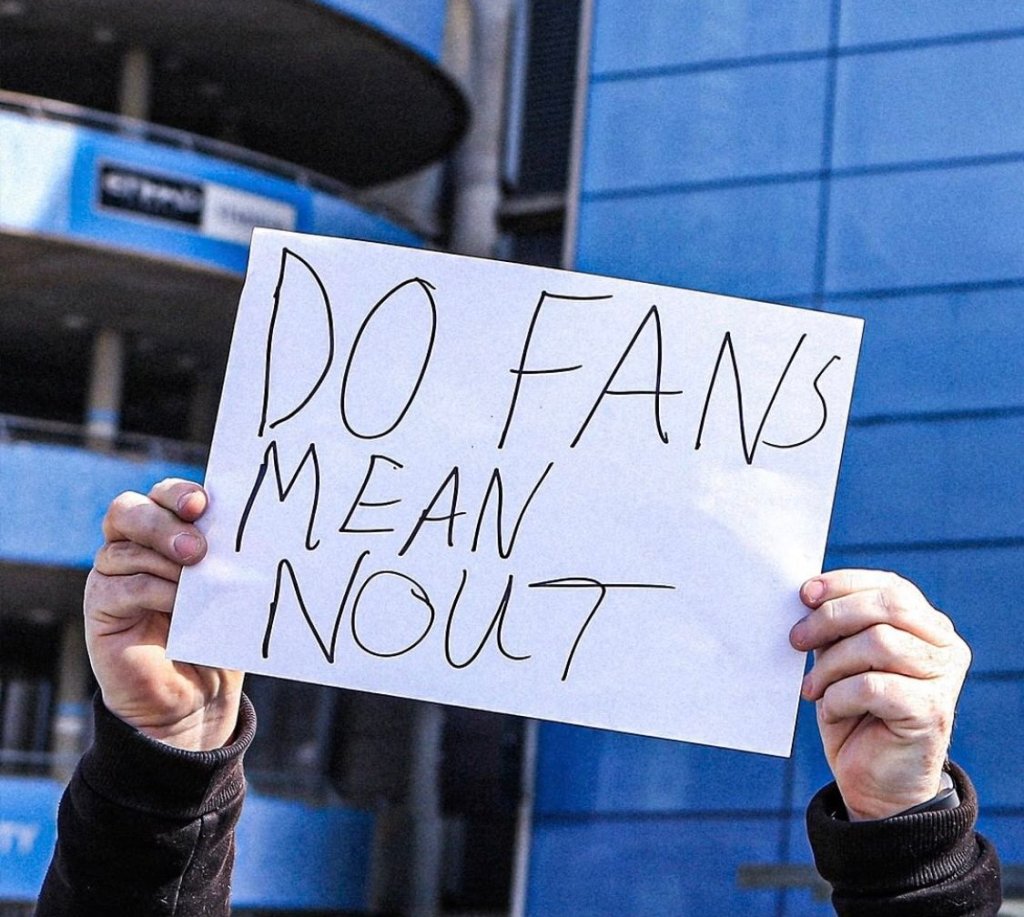

The men’s England squad and their performance in the Euros is not the only relevant football story. The outbreak of protests agains the abortive superleague demonstrated another side of English national culture. English football fans spontaneously made their views on the super league keenly felt. Even the teams who stood to benefit from the new league protested: local pride and identity still count, as do fairness, transparency and participation. It’s okay to play and lose the game, as long as the board is not tilted in one side’s favour. In the wake of rising populism, Brexit and Covid-19 slogans abound: Levelling Up, Building Back Better. Hopefully, these can be put to some use and provide opportunities for reflection and change. For too long, the education system dismisses so many pupils voice before they’d even had a chance to find it.

My politics is on the left which has probably been apparent at several points in this piece. When it comes to the ‘culture war’ issues in most instances I would happily claim allegiance to one side without much truck for compromise. But in the case of the English language it does feel odd that the left-leaning, liberal side is the one arguing for greater protection of English history, culture and heritage, and that the traditionalist, conservative side is advocating for a centralised, homogenisation which will iron out centuries of linguistic variation. Under the ‘culture wars’ currently being waged, many people in England, especially those who are disadvantaged and the ‘losers’ of the inequality divide, are turning towards an insular English identity or worse ethnic-nationalism. My hope is that language and education policy can play their part in fomenting a renewed civic regionalism, celebrating both the diversity and heritage of England.

The above post is an attempt to get down many disparate ideas I’ve been thinking over as a school pupil, university student and English teacher. There’s a lot more I could add, things I’ve missed and credit not given. I’ll try to go back over this eventually and tweak any issues. If there’s something in here you agree with, disagree with or want to talk about more, you can contact me here or on Twitter.

“English is seen as a clear and logical language that, along with the legal system, parliament and railways, was a gift to the rest of the world.”

They were. All systems that require a standard-gauge that everyone can agree on so as to minimise misinterpretation. The English crave order, BSE being that very necessary linguistic rulebook. To pretend that introducing something like Multi-Ethnic London English into the syllabus to be taught alongside BSE and not expect a detrimental weakening effect on general communication is naive verging on disingenuous, innit blud.

LikeLike

I’m not sure why you think learning multiple languages, dialects or varieties would be detrimental.

For instance, do you think there is ‘a detrimental weakening effect on general communication’ in:

– Scotland, where people learn and speak English, Scots and Gaelic

– Catalonia, where people learn and speak Spanish and Catalan

– Indonesia, where people learn and speak Indonesian, Javanese, Tamil, Chinese, Arabic…

LikeLike